|

| Jacob Chemla |

According to his grandson, André, Jacob Chemla (1857-1938) was a scholar and artist. He was an advocate with the Rabbinical Court of Tunis; he was a writer and playwright (Love and Malice was one of his plays); he translated The Count of Monte Cristo and works of Cervantes, among others, into Judeo-Arabic.

After 1881, when the French established their protectorate in Tunisia, Jacob became friends with the architects who were designing the buildings of the new French Administration and restoring some of the historic buildings, and who wanted to clad the buildings with “authentic” Arab tiles--Saladin, Roy, Blondel, and especially Raphael Guy Sadoux. These architects wanted to decorate their buildings with tiles like those on the Bardo Palace and the Mosque of Kairouan.

Jacob Chemla organized a pottery in Tunis with the intent of rediscovering the archaic method of making “Arab” tiles. He experimented with glazes and firing, and in time he “...finally found what he had wanted: beautiful iridescent tiles...that were very close to the old enamels, because, as with the old, Jacob had used local products (sand Mégrine for silica, copper, tin and lead were oxidized and crushed on site). With the help of his son, Victor, the chemist of the company, Jacob developed tiles in the old style.

In 1915 an article in Gustave Stickley’s The Craftsman magazine discussed the effort to renew the old craft of Tunisian pottery and tile-making and the interest this had created in the United States: “...of special interest to us here in America is the introduction of this faience work into our own land, the privilege of importation having been obtained from a family of Tunisian potters by whom the secret of the ancient craft has been preserved.

|

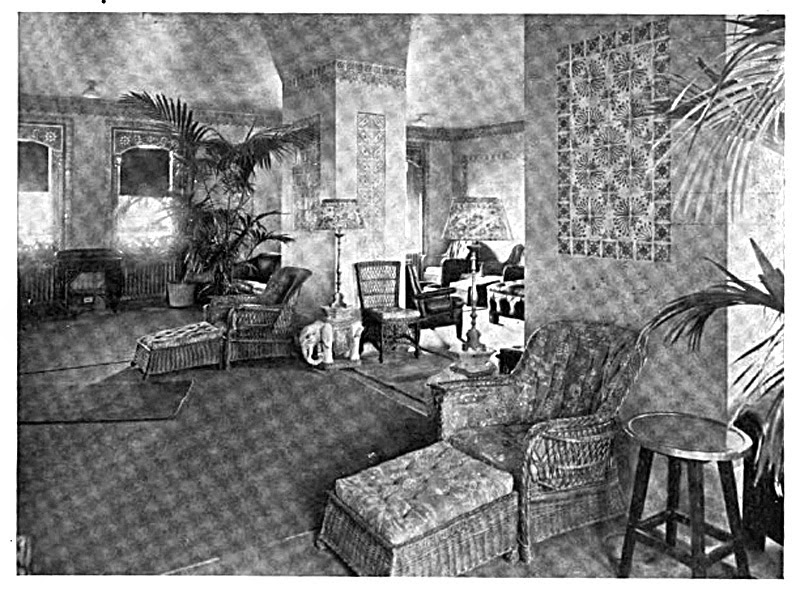

| Tunisian tiles in a wall and bench in the Villa Persane, Tunis. (Photo courtesy of Jeanne Valensi) |

“Some idea of the charm which these tiles add to a garden may be gathered from the photographs [supplied by the Robert Rossman Company], which show the foliage-sheltered grounds and low-walled pathways of the Villa Persane, Tunis.” (“Tiles from the Potters of Tunis: Suggestions for the American Landscape”, The Craftsman, Vol. XXVII, No. 5, February 1915, pp. 584-585)

The Craftsman suggests that its readers visit their Garden Department to see the imported tiles and pottery. “The patterns on many of the pieces are semi-geometric, with here and there a leaf or plant form, suggestions of the pomegranate and the seed pods of the lotus, which give a touch of local character to the designs. ...Occasionally there occur some of the conventionalized leaf forms that one finds in Persian designs.” (Ibid., p. 586)

|

| Tunisian tiles in Dar Marsa Cubes, a bed and breakfast near Tunis. |

Tunisian tiles were “discovered” by the California architect, George Washington Smith, who used them extensively in his Spanish Colonial style of architecture. Other California architects followed Smith’s lead.

|

| Santa Barbara, California City Hall, designed by George Washington Smith. |

|

| Santa Barbara, California City Hall |

|

| Arlington Theater, Santa Barbara, California. Designed by Edwards and Plunkett. (Photo by DillyLynn, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Arlington-fountain.jpg) |

|

| Tunisian tiles in the Santa Barbara County Courthouse. (Photo by Archinia; http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Santa_Barbara_Courthouse_Interior_Room_Detail.JPG) |

Another architect who used Tunisian tiles in California was Bertram Goodhue, and Goodhue also used these tiles in at least one of his New York commissions.

“La Paz”, The Philip W. Henry Residence, Scarborough, NY

One of Goodhue’s commissions was to design a house for Philip Walter Henry (1864-1947) in Scarborough (now a section of Briarcliff Manor), New York. “Philip W. Henry was educated in the public schools of Oxford, New Jersey. After spending 3 years in railway surveying, in 1883 he entered the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York and graduated in 1887. After graduation Henry was employed by the Barber Asphalt Paving Company for fifteen years, first as foreman, then became assistant superintendent for the company at St. Joseph, Montana and Omaha, Nebraska.

Then in New York City, he eventually became vice-president of the company. Beginning in 1902 Henry was a consulting civil engineer and actively involved in various companies and corporations. From 1904-1909 Henry was Vice-President of the Pan-American Company of Delaware. From 1906-1909 he was president of the South American Construction Company, which in 1907-08 built 125 miles of railroad in Bolivia. From 1909-1917 he was president of the Central Railroad of Haiti. In 1910 Henry made a reconnaissance of 700 miles of proposed railways in Spain. ...From 1916-1923 Henry was Vice-President of the American International Corporation in charge of engineering investigations all over the world that were brought to the organization for financing. ...In 1898 Henry studied Spanish to assist in his business and enjoyed the language so much he translated several plays of Calderon de la Barca, a noted dramatist of the 17th century. The most notable of de la Barca’s plays translated by Henry is “La Vida es Sueno” (Life is a Dream) translated in 1921 and staged by the RPI players in March, 1939.” (http://archon.server.rpi.edu/archon/?p=creators/creator&id=104)

There is a passing reference to the Tunisian tiles installed in La Paz in 1917 in a 1920 House Beautiful article: “Much of Mr. Goodhue’s best known domestic work follows English precedent... . On the other hand, he has worked much in the Spanish style, which he handles with ease... . Add to this that the owner has extensive business connections in South America, and that he wished his home, despite its Eastern setting, to have something of the Spanish character... . [The] architect has permitted himself, and has been graciously permitted by the owner, to indulge himself in a bit of fantasy... . The [owner’s bath]room is domed with an alabaster lamp hanging from its apex, and wainscoted with Tunisian tile; (this tile is also used in the little pool in the garden). However, though the effect may be roughly classed as somewhat Oriental, there’s no absence of the most extreme practicality” (“Noteworthy Houses by Well-Known Architects--IV: The Home of Philip W. Henry... . Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, Architect”, House Beautiful, Vol. XLVII, No. II, February 1920, pp. 77, 128)

This house, however, has been extensively “modernized”, and the Tunisian tiles no longer exist. In fact, when he designed the house, Goodhue hired the muralist, Lucile Lloyd, to paint a mural on the Great Hall ceiling, (“Personal and Trade Notes”, Southwest Builder and Contractor, Vol. 57, No. 20, May 13, 1921, p. 14) and this work of art has also been removed.

|

| Master Bathroom, La Paz, c. 2012. (http://www.frequency.com/video/la-paz-scarboro/27662043) |

The McAlpin and Commodore Hotels

At least two major hotels in New York City had Tunisian tile installations. The first was the McAlpin Hotel, built between 33rd and 34th Streets on Sixth Avenue.

|

| A picture post card of the Hotel McAlpin from c.1914. |

“The Hotel McAlpin was constructed in 1912 by General Edwin A. McAlpin... . When opened it was the largest hotel in the world. The hotel was designed by the noted architect Frank Mills Andrews (1867–1948). Andrews also was president of the Greeley Square Hotel Company which first operated the hotel. Construction of the Hotel McAlpin neared completion by the end of 1912... . The hotel underwent an expansion half a decade later. The owners had purchased an additional 50 feet of frontage on 34th street two years early and proceeded to dismantle those properties. The new addition was the same height as the original 25-story building”. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hotel_McAlpin) It was designed by Warren & Wetmore and was known as the Hotel McAlpin Annex. “On the twenty-fourth floor [of the Annex] is located the Turkish Bath and an additional Turkish restroom or dormitory... . This room is decorated with tile inserts furnished by the African Tile Company of Tunis... .” (“Annex to Hotel McAlpin”, Architecture and Building, Vol. L, No. 8, August 1918, p. 53, Plate 141)

|

| Tunisian tiles in the Turkish Rest Room of the Hotel McAlpin Annex. (Plate 141) |

|

| Another view of the Turkish Rest Room. (Photo courtesy of Jeanne Valensi) |

A candy store was designed by John J. Petis and incorporated into the ground floor of the hotel’s annex. The candy store also had Tunisian tile work.

Although the Robert Rossman Company was supposedly the sole importer and supplier of Tunisian Tile Company wares to the United States, the Architecture and Building article states that the tiles in the McAlpin Annex were supplied by the African Tile Company of Tunis. It is not known if the African Tile Company was organized as a separate entity from the Tunisian Tile Company. Each had a different address in Manhattan: a 1920 ad in Scribners magazine for the African Tile Company gives their address as 110 East 59th Street, Manhattan. The African Tile Company used the cat* logo of Albert Chemla. *[In an email to the author, Jeanne Valensi, the grand-daughter of Moses (Mouche) Chemla, wrote "I think the cat you are talking about is really a lion. In fact, in the African Tile Company, it’s described as a lion. It’s a traditional pattern in Tunisian poteries. It’s attached with a chain and is always decorated with a flower on its stomach… ."]

|

| An ad for the “African Tile Company”, which may have been a separate entity organized by Jacob’s son, Albert, or it may have just been another name for Tunisian Tile Products. |

The Tunisian Tile Company, however, advertised its address--which may have been a Robert Rossman showroom--as 23 West 43rd Street. Both, however, were part of the Chemla family potteries.

|

| Undated ad for Tunisian tile products. (Courtesy of Brian Kaiser) |

Robert Rossman also advertised Tunisian tile products in its catalogs.

|

| Page from the 1929 Rossman Tile Corporation Catalog. |

The second hotel in New York City that was known to have used Tunisian tiles was the Commodore Hotel on East 42nd Street near Grand Central Terminal.

|

| Commodore Hotel, a picture post card. (Courtesy of http://www.cardcow.com) |

“The Commodore Hotel was constructed by The Bowman-Biltmore Hotels group. The structure itself was developed as part of Terminal City, a complex of palatial hotels and offices connected to Grand Central Terminal and all owned by The New York State Realty and Terminal Company a division of The New York Central Railroad. The Commodore was named after 'Commodore' Cornelius Vanderbilt, the founder of The New York Central Railroad System, [...and] was designed by Warren & Wetmore... . The Commodore opened its doors on January 28, 1919. ...The Commodore was successful for decades and in June 1967 The New York Central Railroad, which by then was running the hotel...upgraded The Commodore with a 3.4 million-dollar refurbishment. ...By the late 1970s, both the railroad line, now called The Penn Central Transportation Company, and the hotel itself, had become...bankrupt... . At that point, the Trump Organization bought The Commodore. Trump decided to completely rebuild the hotel. The first few floors were gutted down to their steel frame (although the same basic layout of public rooms was retained) and the entire building was transformed with a new reflective glass facade. The only portion of the hotel's decor left untouched was the foyer to the grand ballroom, with its neoclassical columns and plasterwork. The hotel re-opened in 1980 as the Grand Hyatt New York.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Hyatt_New_York)

As one reviewer noted: “With a 20 year tax abatement from the city assuring financial viability and an agreement by the Hyatt chain to manage the new hotel, [Trump] had his architect design a 'slipcover' of reflective glass to install over the original masonry facade... . In what was then a city of tired architecture, his glitterglass remod was a hit and within a couple years was making double the per room rate the old Commodore was making and running at near full occupancy and incidentally kicking off the start of the great NYC real estate boom of the 80s.” (http://citynoise.org/article/8906)

|

| A Tunisian Tile Company installation from the Commodore Hotel. (Photo courtesy of Brian Kaiser) |

What Trump did, however, was destroy the Tunisian tile work in the building, among other artistic desecrations.

The Zeigler Mansion

|

| 2 East 63rd Street, Manhattan. (Photo from http://www.locationdepartment.net/misc,%20resorts,%20etc/8110-a-da.htm) |

This mansion “was built in 1921, commissioned by William Zeigler, heir to the Royal Baking Powder fortune. In a New York Times, 2008 article, Christopher Gray describes some of the innovative techniques used by the architect, Frederick Sterner. These include: creating the appearance of a three-story building by setting back the fourth floor making it almost invisible to the street; a central internal courtyard in the style of a Roman villa; and reducing the rear garden to two small areas either side of the library. Two years later, William Zeigler sold the property to Norman Bailey Woolworth, who used it until 1949 when he donated it to the National Academy of Sciences. It was then purchased in 2005 by Russian businessman Leonard Blavatnik, who has not lived in it but kindly donated the use of the mansion to The Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure ‘Holiday House’.” (http://mhstudioblog.com/2009/12/02/happy-birthday-mh-studio-style/)

The architect of the Zeigler Mansion, Frederick Sterner, was no stranger to the use of tiles as architectural ornamentation. In the first decade of the twentieth century Sterner remodeled his own brownstone near Gramercy Park, at 139 East 19th Street, Manhattan, and made use of Moravian tile work around the entrance to the building.

|

| Tiled entrance to Sterner House, and photo from 1911. |

As Christopher Gray noted, the “town house at 139 East 19th Street was the first building designed in New York by Frederick Sterner, one of the city's most innovative architects. His 1908 complete redesign and renovation of an existing building -- which he did for himself -- was a major achievement for Sterner, then a newcomer to New York, who would go on to bring a touch of color to several of Manhattan's drab brownstone side streets. […In] the summer of 1908 he moved to a block of moldy old brownstones, buying the one at 139 East 19th, between Irving Place and Third Avenue. What to do with mid-19th-century brownstones -- built by the mile, of identical boring design, awkwardly planned and often poorly constructed -- was a subject that puzzled writers at the time… He removed the stoop, covered the dark brownstone with a coat of light cream-colored stucco and replanned the interior. It is now a common approach, but nothing like it had been done in New York before.” (Christopher Gray, “Streetscapes/The Frederick Sterner House, at 139 East 19th Street; An Architect Who Turned Brownstones Into Gems”, The New York Times, June 29, 2003, http://www.nytimes.com/2003/06/29/realestate/streetscapes-frederick-sterner-house-139-east-19th-street-architect-who-turned.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm)

I have found one website with images of most interior rooms and exterior spaces of the Zeigler Mansion, http://www.locationdepartment.net/misc,%20resorts,%20etc/8110-a-da.htm. There are no Tunisian tile installations in this renovated mansion, as far as we can tell.

The twentieth century was a period of renewal of ceramics in Tunisia, especially in Nabeul, where the Chemla family organized a pottery in about 1908. The town of Nabeul became a repository of expertise and was open to the discovery of new techniques by the Jacob Chemla artisans, the Al Kharraz families, Keddidi, Bensedrine and Abderrazak. (A Google translation from: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artisanat_tunisien)

Each of Jacob Chemla’s three sons--Victor, Albert and Moses--worked for varying periods of time in the family’s pottery company. Victor, the chemist and technician, was a good decorator and signed his pieces with a flower. Albert was gifted in public relations, and he also participated in the decoration of many important pieces of pottery, tiles and panels. He signed his pieces with a little humorous cat or lion. (The “cat/lion” trademark can be seen on the ad for the African Tile Company, above.) Moses (aka “Mouche”), Jacob’s third son, was an outstanding designer. He excelled in all kinds of decorations for wall panels, large decorated jars, and Arabic calligraphy. Moses also transformed the various Persian, Turkish and Tunisian styles into a recognizable Chemla tile style. Moses signed his work with a small fish.

The Chemla pottery had many setbacks in its early years, but also some architectural triumphs. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, local architects contacted Jacob and asked him to try to rediscover how to make the colored glazes found on the ancient ceramics of the Hafsides (XIII-XVI centuries), which were lost by the 19th century. According to Jacques Chemla, grandson of Jacob, a major glaze problem was solved in 1910. (From a Google translation of “Ceramics: a family history”, Supplements by Monique Goffard, Lucette Valensi and Jacques Chemla; http://www.chemla.org/ceram2.html) The Chemla Pottery acquired many architectural commissions such as the tile work on the Gare de Bizerte (the tiled railway station, partially destroyed in World War II),

|

| La grande synagogue de la Hara, Tunis and some tiling on its interior. (The exterior picture post card view may be found at http://www.terredisrael.com/comm_juive_Tunisie.php; the interior view may be found at http://www.europeana.eu/portal/record/09323/4FD7338636F36F5F91B7D421C41E5A4394654C9E.html) |

|

| Interior, El Ghriba Synagogue on the island of Djerba. (Photo taken by Chapultepec, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:El_Ghriba.jpg) |

Djerba’s El Ghriba Synagogue*,

|

| One of two still-existing tiled stairways in the Philippeville Train Station (finished in 1937; now the Gare Ferroviaire de Skikda), “designed by architect Charles Montaland...in a Moorish style, the station is an architectural jewel and combines harmoniously with the other buildings designed by the same architect.” (http://skikda.boussaboua.free.fr/skikda_gare.htm) |

the railway station at Philippeville, the Hotel Saint-Georges, Villa Persane in Tunis (the residence of the wealthy consul of the United States), and the Governor’s Palace in Algiers, among others.

*[Jeanne Valensi wrote that she thinks there may not be any Chemla tiles in El Ghriba Synagogue. Lucette Valensi also wrote about Chemla tiling in la grande synagogue de la Hara that was destroyed: "there were Chemla tiles in the old synagogue inside the Hara (the ghetto). It was destroyed in the early 1960s… . [There are no] Chemla tiles in the modern Synagogue built by architect Victor Valensi, and damaged by rioters in June 1967."]

After Jacob Chemla died in 1938, Jacob’s sons, Victor (aka Ai) and Moshe (aka Mouche), took over the helm of the company. After Victor died in 1954 and Mouche died in 1977, Jacob’s grandson, André, continued to design tile panels in Paris.

André also completed a tile mural commission in New York City sometime between 1988 and 1994.

|

| A tax photo taken in 1988 of the building where Bruno Pittini had his hair salon. This facade was built in 1936 with a cast-iron storefront. In 2008 the owners wanted to build a 14 story building and attach the two-story, landmarked facade to the new building. A compromise was reached, and “the 1936 façade, including the diamond-pattern brickwork and side entrance doors were preserved, the open areas flanking the second floor filled in, and three stories rather than 12 erected above and behind.” (http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2014/03/the-ever-changing-no-746-madison-avenue.html) (Photo courtesy of the New York City Department of Records, http://www.nyc.gov/html/records/html/photos/photos.shtml) |

Bruno Pittini (1945-1995) was the creative force behind the 360 Jacques Dessange beauty salons around the world for 25 years. He became a hairdresser in Paris, achieved a reputation as a stylist and developed a fast and unusual cutting technique, cutting hair as though it were fabric. Mr. Pittini opened Bruno Dessange, the high-end, New York hair salon, in 1984, in partnership with Mr. Dessange. (http://www.nytimes.com/1995/11/22/nyregion/bruno-pittini-50-hair-stylist-to-rich-famous-and-beautiful.html) When Mr. Pittini moved into his new salon on Madison Avenue, sometime around 1988, he commissioned André Chemla to design a ceramic tile mural for the salon.

Pittini ordered a mural around 20 meters square, representing Japanese characters nearly two meters tall, with very elaborate kimonos colored in enhanced gold and platinum on a straw yellow background with gold sequins and gold chandeliers. (André Chemla, “L'HISTOIRE DE LA CÉRAMIQUE DES CHEMLA”, http://www.chemla.org/ceram.html) The building above has since had three floors added to its height, and has had a total interior renovation.

|

| An Iznik-style panel designed by André Chemla. (Photo from http://www.andrechemla.com/) |

André “passionately researched the processes, colors and techniques of Iznik ceramics which were the glory of the palaces and mosques of the Ottoman Sultans,” and he created wonderful Iznik-style tiles and pottery which won many awards.

There is much more to the history and development of the ceramics industry in Tunisia, the place of the Chemla family in that development, and the Tunisian Tile Products installations in the United States. My article is only about the few installations in the New York City area, all of which no longer exist. There may be errors in the Chemla family history that I presented from Google translations of the French into English, and if so, my apologies to the Chemla family.

*****

I would like to thank tile preservationist Brian Kaiser for asking me to research the Tunisian tile installations in the New York City area. Brian rescued 3000 Tunisian tiles from the Jackling Mansion in Woodside, California just before Apple CEO, Steve Jobs, had the mansion demolished in 2011. (http://archrecord.construction.com/news/2011/04/110404-Steve-Jobs-House.asp and http://www.cultofmac.com/10656/gallery-beautiful-pictures-of-steve-jobs-abandoned-mansion/10656/)

I would also like to thank blogger Roumi for permission to use his photos of the Gare de Bizerte, if needed.

My thanks also to Lucette and Jeanne Valensi, the daughter and grand-daughter of Moses (Mouche) Chemla, for their help and encouragement.