Before we get to the Béton-Coignet article, an announcement:

|

| "Reflections Series" (http://michaelpadweephotos.weebly.com) |

My photos will be part of a group exhibit called "Generations" from March 8 through June 13 at the Lakefront Gallery, One Hamilton Health Place, Hamilton, NJ 08690. My sister, Lynn, a very talented photographer of nature subjects, will also be exhibiting. If you're in the Princeton, NJ area on March 13, please join us for the opening reception from 5:30PM to 7:30PM, or come and visit another time. (Directions from the NJ Turnpike: Take Exit 7A to I-195 West to Exit 3B (Yardville-Hamilton Square Road). At second light make a left onto Klockner Road. At the next light make a left onto Whitehorse-Hamilton Square Road. The hospital and gallery are on the left.)

*****

Béton-Coignet in New York: The New York and Long Island Coignet Stone Company

My search for answers led me to Francois Coignet (1814-1888) who “...decided to settle near Paris, in the Saint-Denis neighborhood. There in 1852 he opened a...plant where he obtained a patent for cement clinker. Coignet then built a cement factory...using exposed lime walls. He followed the pisé de terre system, rammed earth method of construction, in building the plant. ...Later he took out a patent in England entitled "Emploi de Beton" which gave details of his construction techniques. Coignet started experimenting with iron-reinforced concrete in 1852 and was the first builder ever to use this technique as a building material. He decided...to build a house made of béton armé, a type of reinforced concrete. In 1853 he built the first iron reinforced concrete structure anywhere, a four story house at 72 rue Charles Michels. ...The house was designed by local architect Theodore Lachez.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/François_Coignet)

|

The house of Francios Coignet in Paris. (Photographer: Eric Bajart; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Maison_François_Coignet_2.jpg)

|

Béton Coignet is a name “...given to a beton of very superior quality, or. more properly speaking, an artificial stone of great strength and hardness, which has resulted from the experiments and researches, extending through many years, of M. Francois Coignet, of Paris. The use of beton agglomere in France dates back to the year 1856, and confidence in its value has been constantly on the increase since that date. ...The most important and costly work that has yet been undertaken in this material, is a section, thirty-seven miles in length, of the Vanne aqueduct, for supplying water to the city of Paris. This aqueduct, which traverses the forest of Fontainebleau through its entire length, comprises two and a half to three miles of arches, some of them as much as fifty feet in height, and eleven miles of tunnels, nearly all constructed of the material excavated, the impalpable sand of marine formation known under the generic name of Fontainebleau sand. It includes, also, eight or ten bridges of large span (seventy-five to one hundred and twenty-five feet), for the bridging of rivers, canals, and highways. ...Another interesting application of this material has been made in the construction,...of the light-house at Port Said, Egypt. It will be 180 feet high, without joints, and resting upon a monolithic block of beton[… . Also, an] entire Gothic church, with its foundations, walls and steeple, in a single piece, has been built of this material at Vesinet, near Paris. ...In constructing the municipal barracks of Notre Dame, Paris, the arched ceilings of the cellars were made of this beton, each arch being a single mass. Beton-coignet becomes in process of time as impervious to water as many of the compact natural stones, while its matured strength exceeds that of the best qualities of sandstone, some of the granites, and many of the limestones and marbles.” (From an extract of a report by Major General O. A. Gillmore, Professional Papers, Corps of Engineers, U.S.A., No. 19, in Beton-Coignet: Description of the Material and Its Uses in France and America, Pub. by John C. Goodrich, Jr., N.Y. & L.I. Coignet Stone Co., 1874, pp. 3-4)

“Béton-Coignet...which attracted much attention at the International Exposition at Paris, in 1867, is composed of: lime, 4 parts; hydraulic cement, 1 to 2 parts; and sand, 20 parts. The ingredients are first thoroughly intermixed dry, by hand, and again in a mill, moistening them very slightly with clean water. Moulds are then filled with the mixture, and it is compacted by ramming or hammering. ...It may be made into blocks to be used as cut stone, or may be built up in masses of any desired shape. The cheapness and strength of construction of Béton-Coignet are so remarkable as to have led to its use for even ornamental work. It is used to a considerable extent in constructing the walls of houses and public buildings.” (Robert H. Thurston, A.M., C.E., The Materials of Engineering in Three Parts: Part I, Second Edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1884, pp. 24-25) M. Coignet’s invention “...was merely the observation of a circumstance… . [He discovered how, given] the chemical constituents of any particular stone, to combine them so that all air should be expelled from between the particles, and they should form a homogeneous mass.” (Beton-Coignet: Description of the Material and Its Uses in France and America, Pub. by John C. Goodrich, Jr., N.Y. & L.I. Coignet Stone Co., 1874, p. 17)

The New York and Long Island Coignet Stone Company

That was the "What", now for the "Why New York (and more specifically, Brooklyn)?". “At the start, the [New York and Long Island Coignet Stone Company] was known as the Coignet Agglomerate Company of the United States. It was one of the first firms in the nation to industrialize the production of concrete. [...Two of its officers] traveled to France in the late 1860s and were intrigued by Coignet’s achievements. [John C.] Goodridge [aka Goodrich], Jr. (1841-1900), who was born in Rhode Island and moved to Brooklyn in the early 1860s, attended Williams College and trained at Bellevue Medical College and Long Island Medical College as a surgeon. In 1871 he was listed as the company’s vice president and superintendent of the works, and by the mid-1870s, president. Most publications issued by the company were written by Goodridge, who received several patents related to the manufacture of concrete. [Quincy Adams] Gillmore (1825-88), a member of the Army Corps of Engineers, was the firm’s consulting engineer. A graduate of West Point who lived in Brooklyn Heights and served as a general during the Civil War, he authored numerous papers on fortifications and building materials, including A Practical Treatise on Coignet-Beton and Other Artificial Stone, published in 1871.”

(Landmarks Preservation Commission June 27, 2006, Designation List 378 LP-2202, p. 3)

"The original factory was located near the Gowanus Canal, in what is now called Carroll Gardens, on sixteen lots at the corner of Smith and Hamilton Streets. ...Construction of a new and larger facility began in 1872. Located on Third Avenue, between 3rd and 6th Streets, the site had major advantages.

|

| The New York and Long Island Coignet Stone Company factory site along Third Avenue between Third and Sixth Streets. The Gowanus Canal extension was not there at the time. The company office building can be seen at the corner of 3rd Street and 3rd Avenue. Construction of Whole Foods has not yet begun in this view. (Photo: http://maps.google.com) |

"Not only was it connected directly to the Gowanus Canal and New York Harbor by the recently-constructed 4th Street basin, but it was also close to several developing residential districts.

|

(Beton-Coignet: Description of the Material and Its Uses in France and America, Pub. by John C. Goodrich, Jr., N.Y. & L.I. Coignet Stone Co., 1874, p. 34)

|

In 1872 an Italianate mansion was built on the corner of Third Street and Third Avenue in Brooklyn to serve as the office and showroom for the New York and Long Island Coignet Stone Company. The house was constructed with Béton-Coignet, a form of "cast stone", and served as a model of the work that could be done by this company. In 1874 the Scientific American reported that a “...large new manufactory of béton Coignet has been established...in Brooklyn, N.Y. The works are very extensive, covering an area of five acres, and are capable...of turning out fronts of ten ordinary houses per day, besides a large quantity of fine ornamental work, giving constant employment to one hundred hands. The process of manufacturing consists in first grinding down the constituent elements of the stone to be imitated, and mixing them by machinery until they reach a plastic state. The moulds are then filled by a peculiar process which entirely excludes the air, and are immediately removed. The stone, within a few days, is ready for transportation, and continues to increase in density. The béton is impervious to water; and...withstands the effect of frost...and will withstand a crushing pressure of about four tons to the square inch.” (“Beton Coignet Artificial Stone for Ornamental Architecture”, Scientific American, Vol. XXX, No. 15 (New Series), April 11, 1874, p. 231)

“The practice of using cheaper and more common materials on building exteriors in imitation of more expensive natural materials is by no means a new one. ...Cast stone was just one name given to various concrete mixtures that employed molded shapes, decorative aggregates, and masonry pigments to simulate natural stone. ...Francois Coignet… received United States patents in 1869 and 1870 for his system of pre-cast concrete construction... . In 1870 Coignet's U.S. patent rights were sold to...John C. Goodrich, Jr., who formed the New York and Long Island Coignet Stone Company.” (Richard Pieper, “Preservation Brief 42”; http://www.oldhouseweb.com/how-to-advice/preservation-brief- 42.shtml)

When I first moved to Brooklyn in 1978, I had been told that this building--which was landmarked by New York City in 2006, but had been allowed to deteriorate by past owners--was the gatehouse to the Litchfield Villa, which is between 3rd and 5th Streets in Prospect Park. This was not the case, however. Despite its successes, the Coignet company filed for bankruptcy in 1873 and the factory closed in 1882. As a result of the Coignet Stone Company’s originally successful operations, Edwin C. Litchfield, whose family owned much of the land in Park Slope, decided to reactivate the Gowanus creek as a working waterway for transport of raw and finished materials, and after 1882 this building was used by Litchfield as the office for his Brooklyn Improvement Company (until 1957), which was responsible for the residential development of Park Slope, among other projects. (http://hensonarchitect.com/2012/03/)

The building is described as follows in the Landmarks Preservation Commission Designation Report: “The NY and LI Coignet Stone Company Building is located at the southwest corner of Third Avenue and Third Street in the Gowanus section of Brooklyn. It is two stories tall and set on a raised basement with small rectangular windows. All but the three-dimensional elements are faced with a non-historic, red faux brick. Most of the details, such as columns, quoins, and keystones are made of concrete and are painted with a cement wash. There are two chimneys, faced with faux brick. ...The Third Avenue façade is divided into three bays. Below the first story, the basement is faced with rusticated panels, interrupted by circles. The first and second story is divided by an entablature. At the level of the roof is a simple entablature. The central bay contains an arched entrance set behind an Ionic portico. ...The Third Street façade resembles the Third Avenue façade, displaying a similar arrangement of identical features.” (Landmarks Preservation Commission June 27, 2006, Designation List 378 LP-2202, p. 8)

This building is not the only structure in Brooklyn built with béton coignet. The original 113’ diameter fountain designed and built at the entrance plaza for Prospect Park (now Grand Army Plaza) was made of béton coignet. In 1873 it was reported that “The new fountain at the entrance of the plaza at Prospect Park is now very nearly complete. The dome for this fountain, of which Mr. Calvert Vaux is the architect, is made by the New York and Long Island Coignet Stone Company of Brooklyn, and is of beton-coignet—an artificial stone of great strength and beauty. The design and workmanship is said to be finer than any work of similar character in the United States. The whole dome is elaborately ornamented with appropriate designs; is so carefully put together, and so ingeniously constructed, that no joints are visible and the whole mass is firmly bound together. The open spaces on the dome are to be covered with colored glass. Inside of this gas jets, lighted by electricity, will during the night give a most beautiful effect. The water cone plays from the dome and falls back into the fountain through a hundred jets.” (Beton-Coignet: Description of the Material and Its Uses in France and America, Pub. by John C. Goodrich, Jr., N.Y. & L.I. Coignet Stone Co., 1874, p. 47)

|

(The Cleft Ridge Span in Beton-Coignet: Description of the Material and Its Uses in France and America, Pub. by John C. Goodrich, Jr., N.Y. & L.I. Coignet Stone Co., 1874, p. 25)

|

Also built in Prospect Park was the Cleft Ridge Span, the first continuous, arched bridge span made of béton coignet in the United States. In 1872 John Y. Culyer, the Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Parks Commission, wrote: “Early in the season the New York and Long Island Coignet Company resumed work on Cleftridge Span, and completed so much of the arch as remained unfinished at the date of my last report. The roadway over the arch was thrown open to the public early in spring. An ornamental pavement of Coignet stone has been laid under the archway. All of this work has satisfactorily withstood the effects of a winter and summer exposure, exhibiting no marked signs of disintegration or other material defect. And, in April 1873 John Y. Culyer further wrote, “A bridge, built under my supervision in Prospect Park, in the winter of 1871-2, under the most trying circumstances, perhaps, has now been subjected, substantially, to the action of two winters, and without any impairing results, and I have no doubt as to its continued durability.” (Beton-Coignet: Description of the Material and Its Uses in France and America, Pub. by John C. Goodrich, Jr., N.Y. & L.I. Coignet Stone Co., 1874, pp. 30, 24)

|

A 2008 photo of the Cleft Ridge Span in Prospect Park. (Photographer: Dave Smith)

|

“This archway was at first designed to be formed of granite and brick, but the Long Island Béton-Coignet Company offered to make the whole [span] of their patented stone. The architect, Mr. Calvert Vaux, agreed to this and the experiment has proved satisfactory. The principal advantage of this material for decorative purposes lies in the facilities it offers for the introduction of ornamental detail, because after a design for recurring ornament is once well modeled and prepared for carving, it can be repeated again and again with ease and precision. In the architectural treatment of archways for park purposes the most serious difficulty lies in the arrangement for the soffit or ceiling, the surface of which is always so large that its elaboration in brick, stone, or wood is only admissible in very prominent situations on account of the cost involved. Under these circumstances the soffit of the arch becomes the key-note of the design, and in the Cleftridge Span this part of the work has been made over its whole surface of a very rich and elaborate pattern. The archway is now completed, and the result is sufficient to show that it [...is] a valuable addition to the decorative resources of the architect.” (From the New York World, March 9, 1873 as quoted in Beton-Coignet: Description of the Material and Its Uses in France and America, Pub. by John C. Goodrich, Jr., N.Y. & L.I. Coignet Stone Co., 1874, p 53)

|

| 576-568 Atlantic Avenue. The buildings from 562 to 578 Atlantic Avenue, at the junction of Atlantic, Fourth and Flatbush Avenues, and 118 Flatbush Avenue are of concrete construction with concrete architectural elements. Although I have not found records that tie these buildings to the N.Y. & L.I. Coignet Stone Company, the architectural elements are mass produced concrete and the buildings are four stories high. The interactive NYC map, however, states that these buildings were built in 1910, which may or may not be accurate. |

Forty-Seven other buildings built of béton coignet in New York City are as follows: "Thirty buildings for use as stores and offices, four stories in height, at the junction of Flatbush and Atlantic avenues, in course of construction by Mr. Vreeland, eight being already finished.

|

Four buildings of béton coignet built by A.S. Barnes on Clinton Avenue, Brooklyn in 1872. (Beton-Coignet: Description of the Material and Its Uses in France and America, Pub. by John C. Goodrich, Jr., N.Y. & L.I. Coignet Stone Co., 1874) Many members of the Barnes family lived in the Clinton Hill area: Alfred S. Barnes, founder of the family fortune, lived in a large frame mansion at 533 Clinton Avenue. (New York City Landmarks Designation Report for Clinton Hill, p. 73) The NYC integrated map (http://maps.nyc.gov/doitt/nycitymap/) shows these houses as incorrectly being built c. 1899 rather than in 1872. Perhaps that is the earliest record for these properties at 536-540 Clinton Avenue?

|

"Five three-story and basement dwellings, by A. S. Barnes, on Clinton avenue, near Atlantic.

"Five three-story and basement dwellings, by Mr. McCord, in the same section [not found by me]. A building by Mr. Olsen, corner of Fourth avenue and Dean street, three stories in height, the first floor being for a store and the upper portion for a dwelling.

|

| 50 Fourth Avenue, Brooklyn. The only building constructed with concrete on a corner of Dean Street and Fourth Avenue. The interactive NYC map states this building was constructed in c.1899, which, again, may or may not be accurate. |

"...The arches, columns and traceries of the great Roman Catholic Cathedral, corner of Fifth avenue and Fiftieth street, New York, were also manufactured by this Company… . The windows and traceries of a church built at Staten Island by Mr. D. Appleton, the publisher, are also of this substance. The Plaza of the Woodsburgh Pavilion, at Rockaway, contains fourteen thousand square feet of the agglomerate, which has also been extensively used in the construction of public buildings on Ward’s island.” (Beton-Coignet: Description of the Material and Its Uses in France and America, Pub. by John C. Goodrich, Jr., N.Y. & L.I. Coignet Stone Co., 1874, p. 38) Also, “At the recommendation of Gen. Q. A Gillmore, [béton coignet] has been used in the construction of the casemates*, sally-ports, floors etc., of Fort Wadsworth, Staten Island.” (John C. Goodrich, Jr., p. 50)

*[Casemates are fortified gun emplacements or armored structures from which guns are fired. Originally, the term referred to a vaulted chamber in a fortress. A sally port is a secure, controlled entryway, as in a fortification.]

St. Patrick's Cathedral

|

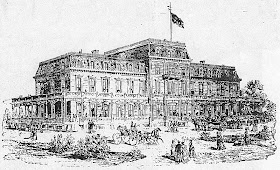

| ( Photo from http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NHLS/Photos/76001250.pdf) |

"[St. Patrick's Cathedral] was designed by James Renwick, Jr. in the Gothic Revival style. On August 15, 1858, the cornerstone was laid [at the corner of 50th Street and Fifth Avenue]. At that time, present-day midtown Manhattan was far north of the populous areas of New York City.

The cathedral and associated buildings were declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976. (http://www.nyc-architecture.com/MID/MID054.htm)

Nowhere in the Landmarks forms have I seen an architectural description that mentions béton-coignet in the construction of the cathedral. However, the "arches, columns and traceries" manufactured for this cathedral by the NY and LI Coignet Stone Company were interior features:

|

| Interior of St. Patrick's Cathedral showing some of the areas 30' above the floor which were made with béton coignet. (Photo taken from the SkyscraperPage.com forum: http://forum.skyscraperpage.com/showthread.php?t=203942) |

"Inside the cathedral...marble reaches only about 30 feet above the floor. In a 19th-century economy move, the builders of the interior switched from marble to a material called Beton Coignet, also known as artificial stone. Above the concrete walls are ceiling vaults of plaster." (http://forum.skyscraperpage.com/showthread.php?t=203942)

The Woodsburgh Pavilion , 1870-1901

* A "dummy-car" on a railroad was a car containing its own steam power or locomotive. (http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Dummy+car)

|

| The Woodsburgh Pavilion. (Five Towns Local History blog; http://ftlh.blogspot.com/2011/07/woodmere-pavilion-1870-1901.html) |

"Mr. Samuel Wood, a liquor vendor, purchased a portion of the land which was known as Near Rockaway and named it Woodsburgh after his family name. He bought this land in 1869 intentionally as a summer resort area for the wealthy. Mr. Wood built two hotels, the Woodsburgh Pavilion and Neptune House... . He also sold large tracts to Millionaires to build summer homes. ...After Samuel Wood died in 1878, this property came into the possession of Abraham Hewlett and the Woodmere Land Improvement Company, who continued its development." ("The History of Woodmere"; http://hefner110.pbworks.com/w/page/11704390/Neighborhood%20History)

Samuel Wood hired "One hundred and fifty men [to work] steadily through the winter of 1869-70 in the hope of opening the resort the following summer. The first structure to be built was the railroad depot, followed by the Grand Hotel or Pavilion, a smaller hotel (later called the Neptune), five cottages and the Boulevard, which extended in a straight line from the railroad tracks to the bay.

"The Pavilion sat on an elevated area in the center of town, at the intersection of Woodmere Boulevard and Broadway. Built in the shape of a Greek cross, it was 175 feet long and 60 feet wide. It consisted of the four-storey main building and two three-storied wings, surrounded by a two-storied piazza." (http://ftlh.blogspot.com/2011/07/woodmere-pavilion-1870-1901.html)

This piazza is probably the "Plaza of the Woodsburgh Pavilion, [...which] contains fourteen thousand square feet of [béton-coignet]," written about in the Landmarks Nomination Form. However, there do not seem to be any surviving photographs of this hotel which would confirm this.

Béton-coignet was once a major form of compressed and molded concrete used worldwide. It was exceptionally strong and resistant to weather-related deterioration, and it could be molded into just about any shape for structural and ornamental use. It was important to Brooklyn because it was produced and used here architecturally. Béton-coignet is almost forgotten now, and only a very few of its constructs still survive. All of the survivors, though, should be identified and protected as they are part of our historic architectural heritage.

This, however, does not seem to be very high on the Landmark Preservation Commission list of priorities. A new and large crack in one of the walls of the N.Y. and L.I. Coignet building next to Whole Foods was noticed in mid-December: "Construction on the about-to-open Whole Foods Market caused a massive crack in the wall of a historic building that shares the lot with the health food giant, claim locals who...say the city is not doing enough to protect it." (Megan Riesz, "Whole Foods on crack: Not us!", The Brooklyn Paper, Vol. 36, No. 50, Dec. 13-19, 2013, p. 1) It remains to be seen if this 140 year old building will withstand the tender care of Whole Foods construction and the New York City agencies that are responsible for oversight.

*****

A Second Announcement:

March 26 - September 7, 2014:

is coming to New York. This popular exhibit about the R. Guastavino Company will be on view at the Museum of the City of New York.

Your articles are a delight, and the documentation is supported by impressive research. Thanks very much.

ReplyDeleteAs for the dating the four story buildings at 576-568 Atlantic Avenue and the corner building at 50 Fourth Avenue, Brooklyn, they are obviously those identified in your research. A comparison of these buildings with that of turn-of-the-century speculative buildings shows significantly different architectural detailing. City records are often incorrect, so I would trust your research, based as it is on contemporary sources.

Again, thanks for your impressive research and writing.