|

| The old City Hall subway station (now closed) from The Brickbuilder , Vol. 13, No. 4, April 1904, p. 85. |

In 1904 the City Hall Station "...was the City's pride and joy, the flagship station of the long-awaited subway system. Located on a loop of single track, the station presented...unique design possibilities: the platform and track could be bridged by a single snug arch; the...[R. Guastavino Company's] special system of setting tiles in a criss-cross pattern with fast-setting mortar created lightweight, centerless vaults... . ...the arches and vault ribs are edged with colored tile, and there are name plaques on the walls and over the stairway from the platform." (Lee Stookey, Subway Ceramics: A History and Iconography, published by Lee Stookey, Brooklyn, NY, 1992, p. 20)

The 1979 Report to the Landmarks Preservation Commission describes the tilework of this station. "The curve of the vaults is ideally suited to the curved configuration of the station as it follows the single loop track. The vaults are constructed of white mat-finished tiles with contrasting green and brown glazed tiles at the edges of the vaults. The younger Rafael Guastavino was especially interested in the development of ornamental and colored ceramic tile for Guastavino vaults. ...Decorative faience plaques in brown, blue, and white with the inscription 'City Hall' are set in the side walls. A large name tablet adorns the arch above the wide staircase leading from the platform to the entrance area." (Marjorie Pearson with David Framberger, Landmarks Preservation Commission Report, Designation List 129 LP-1096, October 23, 1979)

This station was closed in 1945 and is currently used as a turn-around loop for the No. 6 local train.

|

| A stable on Long Island with Guastavino vaults from The Brickbuilder, Vol. 13, 1904 |

|

| "Dome of Elephant House", New York Zoological Park, Bronx, NY (From: Charles H. Hughes, "Interesting Examples of the Use of Burnt Clay in Architecture", The Brickbuilder, Vol. 18, No. 8, August 1909) |

buildings. The Guastavino Company was founded in 1888. "In the late 19th and early 20th century, Rafael Guastavino Moreno and his son Rafael Guastavino Exposito were responsible for designing tile vaults in nearly a thousand buildings around the world, of which more than 600

|

| Interior view, Amity Baptist Church (demolished) 312 West 54th Street, Manhattan, 1909 (see citation above) |

"Born in Valencia in 1842, Rafael Guastavino i Moreno went to Barcelona in 1861 to train as a builder at the Escuela de Maestros de Obras. By 1866, his precocious professional vision had driven him to start his career as builder and architect even before graduating.

His arrival in the United States in 1881 with his son Rafael Guastavino i Expósito, the subsequent founding of his own building company in 1888, the modernization of the traditional laminated tile system and his business vision all led to the reinvention of a new type of public space for the modern American metropolis —space that was excavated from within the architecture itself, conferring an urban dimension to its interiors. The Guastavino Company participated in many of the emblematic buildings of the time in collaboration with the most prestigious American architects. The clarity, texture and geometry that characterize Guastavinian vaulted spaces have invariably been identified with the modern American metropolis which, for the first time, expressed its desire to become a historic city." (http://www.rafaelguastavino.com/en/)

The tilework on the exterior of the dome of the Elephant House, above, is somewhat reminiscent of the later Guastavino dome on the State Capitol Building in Lincoln,

Nebraska. On the interior of this building the Guastavino Company worked with the mosaic designs of Hildreth Meière to produce works of art on the walls and ceilings.

|

| Eight Winged Virtues |

meticulous attention to color, many tiles 'required two and three glaze firings at different temperatures.' Despite this great care, 'Hildreth Meière was a perfectionist and rejected many tiles so the manufacture of many extra batches of tiles became a necessity'." (John Ochsendorf, Guastavino Vaulting: The Art of Structural Tile, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2010, pp. 173-174)

In the early years of the twentieth century Rafael Guastavino Jr. experimented with lustre glazes on tiles. In time he developed a series of stable lustre glazes and made reproductions of Spanish and Persian lustre ware.

|

| From: Rafael Guastavino, "Lustre Pottery", The Clay-Worker, Vol. 74, No. 3, September 1920, pp. 215-216 |

|

| (Photo taken, with permission, of a framed drawing on a wall of the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York) |

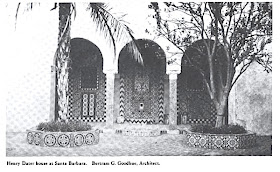

The Dater Residence, "Built in the North African manner...was a contrast in styles: plain wall surfaces and simple blocklike forms surrounding a patio covered in tiles. An article on new California houses in Country Life (1920) describes the tiles as being designed by the architect, and the drawings and factory order cards...point to the Guastavino Company as the source of these tiles." (Janet Parks and Alan G. Neumann, The Old World Builds the New: The Guastavino Company and the Technology of the Catalan Vault, 1885-1962, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library and the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, New York, New York, 1996, pp. 36-39)

|

| Guastavino tilework, exterior of the Dater Residence, Montecito, California |

And, at the entrance to Prospect Park at Grand Army Plaza, there are two small dodecahedral structures with Guastavino domes.

In another post I will discuss some of the artistic contributions of the Grueby, Rookwood and Hartford Faience tile and pottery companies, and the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company to the City's subway system in the Heins and LaFarge era.

No comments:

Post a Comment