Art Deco style in architecture blended parts of many different art movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. “The art deco style, which above all reflected modern technology, was characterized by smooth lines, geometric shapes, streamlined forms and bright, sometimes garish colours. [...Art Deco] influences include the geometric forms of Cubism..., the machine-style forms of Constructivism and Futurism, and the unifying approach of Art Nouveau. Its highly intense colours may have stemmed from Parisian Fauvism. Art Deco borrowed also from Aztec and Egyptian art, as well as from Classical Antiquity. Unlike its earlier counterpart Art Nouveau, however, Art Deco had no philosophical basis - it was purely decorative.” (http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/history-of-art/art-deco.htm)

|

| The Chrysler Building as seen from the Empire State Building. (Photo in the Public Domain, taken by Misterweiss) |

Art Deco architecture used new materials to express a style that was exemplified by streamlined lines, stepped setbacks, ziggurats, pyramidal and chevron shapes, sweeping curves and stylized sunbursts. Art Deco “...contrasted sharply with the fluid motifs of Art Nouveau[.] Art Deco architecture represented scientific progress, and the consequent rise of commerce, technology, and speed.” (http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/history-of-art/art-deco.htm)

The three buildings I'll look at today--the Chrysler Building, the Film Center Building, and the Kent Garage/Sofia Brothers Storage Warehouse/The Sofia--have facades that have all been designated New York City landmarks. Only two, however, have an elusive and exceptional interior landmark designation for their public spaces.

|

| Detail of the ornamentation on the upper tower of the Chrysler Building. (Photo from Wikipedia, taken by Postdlf in 2005) "[...On] the Chrysler Building the entire upper section above the 61st floor -- and much of the ornament below -- is gleaming chrome-nickel steel, which reflects sunlight with dazzling brilliance. To withstand corrosion, the architect specified a particular steel developed by Krupp, the German steelworks, called Nirosta. ...The metal is generally soldered or crimped -- all by hand -- and the thick, wavy solder lines and the irregular bends all betray individual craftsmanship. The broad surfaces of metal, almost all stamped to form on the site, are wavy and bumpy, like giant pieces of hand-finished silver jewelry." (Christopher Gray, "Streetscapes: The Chrysler Building;Skyscraper's Place in the Sun", The New York Times, December 17, 1995; http://www.nytimes.com/1995/12/17/realestate/streetscapes-the-chrysler-building-skyscraper-s-place-in-the-sun.html |

In 1928, three years after his automobile manufacturing company was founded, Walter P. Chrysler located a property on which to build his corporate headquarters--the northeast corner of Lexington Avenue and Forty-second Street. Work by an architect, William Van Alen, had already begun on a building for the Reynolds Company on this property, but that leasehold was lost. Chrysler then leased the property, kept the architect, but changed the building plans. Chrysler's building was to become a “cathedral of modern industrial design.”

“Completed in 1930...its powerful granite foundation, missile-like brick tower, stainless steel ornamentation glorifying the automobile, gleaming seven-story stainless steel spire, and intense, motivational murals converge in praise of the possibilities of mind and machine in the new industrial era.” (John B. Stranges, “Mr. Chrysler's Building: Merging Design and Technology in the Machine Age”, ICON: Journal of the International Committee for the History of Technology, Volume 20, Number 2, 2014, p. 1)

|

| Four drawings of the Chrysler Building showing its design evolution. ("Chrysler Building Opened 85 Years Ago Today", Driving For Deco blog; http://www.drivingfordeco.com/chrysler-building-opened-85-years-ago-today/) |

“Completed in 1930...its powerful granite foundation, missile-like brick tower, stainless steel ornamentation glorifying the automobile, gleaming seven-story stainless steel spire, and intense, motivational murals converge in praise of the possibilities of mind and machine in the new industrial era.” (John B. Stranges, “Mr. Chrysler's Building: Merging Design and Technology in the Machine Age”, ICON: Journal of the International Committee for the History of Technology, Volume 20, Number 2, 2014, p. 1)

|

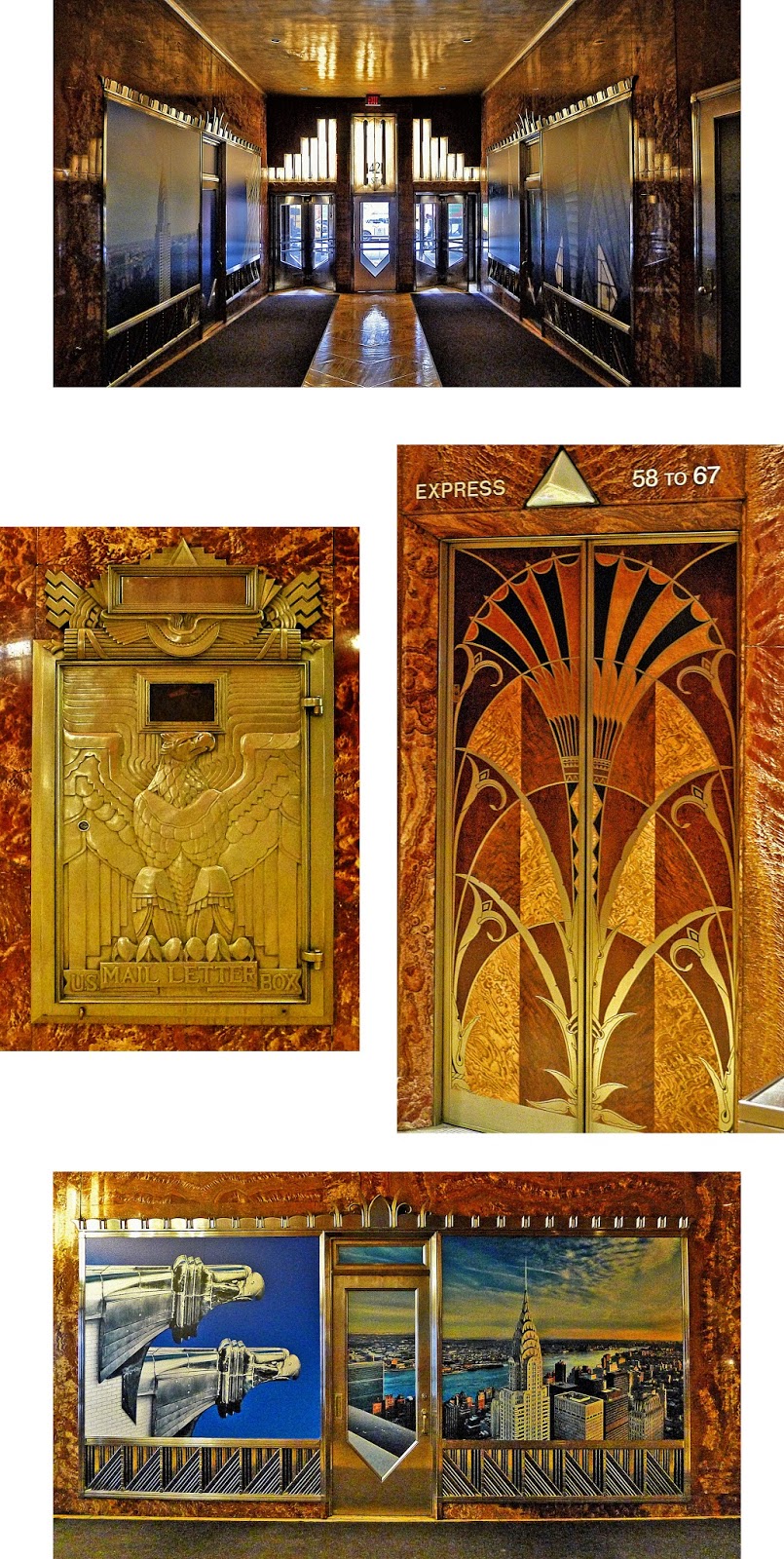

| The Lexington Avenue entrance. (Color photos courtesy of Michael Padwee unless otherwise noted) |

“Standing 319.5 meters (1048 feet) high, the Chrysler Building houses 77 floors, including a lobby three stories high with entrances from three sides of the building, Lexington Avenue, 42nd and 43rd Streets.” The lobby has a triangular form which is “lavishly decorated with Red Moroccan marble walls, sienna-colored floor, onyx, blue marble and steel. Artist Edward Trumbull was hired to paint murals on the ceiling... .” (Megan Sveiven, “AD Classics: Chrysler Building / William Van Alen”, Arch Daily, December 22, 2010; http://www.archdaily.com/98222/ad-classics-chrysler-building-william-van-alen)

|

| The lobby with three views of the ceiling mural. The mual is "36 meters long by 26 meters wide[;...and the] images represent...progress, transport and energy." (https://en.wikiarquitectura.com/index.php/Chrysler_Building#Concept) |

“Art deco designers loved large murals as a way of completing 'unity of design'. Chrysler himself saw the creation of a ceiling mural in the lobby as an opportunity to express his most deeply-felt view of the era in its most condensed and personal form. For Chrysler, modern life revealed itself most fundamentally in the revolutionary inventions in transportation - the locomotive, automobile and airplane - and in a new creative class of engineers, scientists and businessmen whose ingenuity made these inventions possible.” (John B. Stranges, “Mr. Chrysler's Building: Merging Design and Technology in the Machine Age”, ICON: Journal of the International Committee for the History of Technology, Volume 20, Number 2, 2014, p. 12)

"Edward Trumbull (1884-1968) was one of the foremost American muralists of his generation. ...The mural in the Chrysler Building...is divided into several parts, each with its own theme. A triangular panel placed over the information booth displays a large muscular Atlas figure. Radiating out from this are three bands which follow the triangular form of the main concourse. The first showing a series of abstract patterns and lines, was supposed to symbolize primitive, natural forces. The second, depicting construction workers and techniques, has a specific analogy to the construction of the Chrysler Building. The third shows the development of modern transportation with an emphasis on airplanes. Extending outward over the Lexington Avenue entrance lobby is a large panel with a rendering of the building as seen from the exterior." (Landmarks Preservation Commission, September 12, 1978, Designation List 118, LP-0996, p. 5; http://www.neighborhoodpreservationcenter.org/db/bb

|

| Four views of ornamentation in the lobby. |

"One of the most dramatic and striking features of this interior is the lighting system. Vertically placed panels of polished Mexican onyx are placed in a stepped pattern above the elevator halls and the three street entrances. Vertical reflector troughs of 'Nirosta' steel set with lamps are placed in front of the onyx panels. As the light is reflected off these panels[,] it is given an amber glow. ...The octagonal piers in the main concourse also provide a [similar] light source." (Landmarks Preservation Commission, September 12, 1978, Designation List 118, LP-0996, p. 4; http://www.neighborhoodpreservationcenter.org/db/bb

_files/78CHRYSLER-INT.pdf)

Two public areas of the Chrysler Building that were exceptional Art Deco treasures had disappeared before landmark designation was even considered for the lobby. At one time a Chrysler automobile showroom occupied part of the lobby. This may not have been part of the main concourse as the pier lighting is different and there's no ceiling mural in this area.

|

| (Reinhard & Hofmeister, A., Gottscho, S. H., photographer. (1936) Master prints. Chrysler showroom, Chrysler Building, New York city. photographed Dec. 6. [Image] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/gsc1994028989/PP/) |

The other "public" area was on the 67th floor of the building. "The Cloud Club[, which began as a three-level members club and speakeasy,] once belonged to a group of mile-high power lunch spots in New York City atop the city’s most distinctive skyscrapers. It was initially designed for Texaco, which occupied 14 floors of the Chrysler Building, and used as a restaurant for executives. It opened with 300 members of New York City’s business elite. The Cloud Club had an eclectic mix of design, ranging from Futurist in the main dining room, Tudor for the lounge, and an Old English grill room. Perhaps because of its decor, or its original function, it never became hip and stylish like the Rainbow Room but it did have amenities like a barber shop and locker rooms that were used to hide alcohol during Prohibition." (http://untappedcities.com/2015/02/19/top-10-secrets-of-the-chrysler-building-in-nyc/)

The Cloud Club operated until 1970, and it was demolished in the 1980s.

|

| Two views of the Cloud Club. (Photo credits: http://www.decopix.com/art_deco_photo_galleries/the-cloud-club/) |

When I first moved to New York City in the mid-1960s, I was employed as a caseworker for the Department of Welfare, and I worked in the Veterans’ Welfare Center on the fifth floor of the Film Center building. I don’t remember ever noticing the lobby during the six months I worked there, possibly because the welfare center employees and clients were told to use a separate entrance and elevator, which only went to the fifth floor.

|

| The central, four-window bay of the Film Center building, 630 Ninth Avenue between 44th and 45th Streets. |

The Film Center Building and its lobby became New York City landmarks in 1982. The Landmark Designation Report states that “[the] Film Center Building originally was built as a support facility for the motion picture industry centered in Times Square to the east. Although much of that industry has departed, the Film Center Building still serves the functions for which it was built. The early development of Times Square, and the blocks east and west of Broadway, consisted of new theaters for the ‘legitimate stage.’ In the 1910s and 1920s, however, the new motion picture industry moved into the district. The industry at that time was headquartered in and around New York City. ...With so much of the motion picture industry concentrated in the area, it was not unnatural that support services would locate nearby, in the less expensive section west of Eighth Avenue. ...Ten years after its completion, the Film Center Building housed over 70 film distributors, who sent films to theaters all over the city.” (Landmarks Preservation Commission November 9th, 1982; Designation List 161 LP-1220, p. 1-2;

http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/1220.pdf)

Françoise Bollack and Tom Killian write about the Film Center interior in their monograph about Ely Jacques Kahn. They wrote that the “Film Center lobby dazzles with its showy, unrestrained and riotous use of color and shape: Frank Lloyd Wright, Arts and Crafts and Precolumbian architecture are all present here. The colored glass mosaics, the terrazzo, the brass decorative elements, the gusto with which the Architect ‘sails merrily into experiment’ give the space a bouyant feel, as if an impish Mayan God were looking at us through the shimmering wall surface, ready to play tricks.” (Françoise Bollack and Tom Killian, Ely Jacques Kahn New York Architect, Acanthus Press, New York, 1995, p. x)

|

| As you walk into the Film Center Building, you’re greeted with this view of the lobby. |

|

| The bronze elevator doors and an abstract, polychrome glass mosaic mural are behind the lobby desk. “In a relatively limited area, architect Ely Jacques Kahn ingeniously used color as a structural element rather than solely as decoration. Bold black-and-silver bands wrap the walls to expand the narrow space, and bright mosaics echo geometric motifs popular in the period.” (http://landmarkinteriors.nysid.net/gallery/film-center-building/) |

The lobby is also described in the Landmark Designation Report: “The Film Center interiors are the product of Kahn's highly individualistic version of the Art Deco style. The relatively small spaces are transformed into a highly decorative formal entrance through his unusual technique of treating walls and ceilings like woven plaster tapestries, and his polychromatic treatment of both individual elements, such as the elevator doors and mailbox, and strictly decorative additions, such as the elaborate mosaics and stylized movie cameras. Even radiator vent grilles and staircase risers are brought within the ornamental scheme.” (Landmarks Preservation Commission November 9th, 1982; Designation List 161 LP-1220, p. 1;

http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/1220.pdf)

|

| Detail of the glass mosaic designed by Kahn. |

|

| A section of the wall and ceiling over the entrance doors. |

“Much of Kahn's architectural thought was influenced by his interest in the decorative arts particularly his notions about color and ornament. In a 1929 [essay,] ‘On Decoration and Ornament,’ [Kahn] wrote:

'The new attitude in design proceeds to

consider decoration from a new angle.

Decoration is not necessarily ornament. The

interest of an object has primarily to do with

its shape, proportion and color. The texture

of its surface, the rhythms of the elements

that break that surface either into planes or

distinct areas of contrasting interest, becomes

ornament.'

"Kahn provided ‘texture’ to his buildings by treating the walls like woven fabric, an effect that became fairly common in Art Deco buildings. The idea that walls should be designed along the principles of textiles has been traced back to the German architect, Gottfried Semper (l803-1879), who included as one of the four basic components of architecture the ‘enclosure of textiles, animal skins, wattle or any other filler hung from the frame of...supporting poles.’” (Landmarks Preservation Commission November 9th, 1982; Designation List 161 LP-1220, p. 3;

http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/1220.pdf. See also, Françoise Bollack and Tom Killian, Ely Jacques Kahn New York Architect, Acanthus Press, New York, 1995, pp. 20-21.

|

| Bronze elevator door; bronze wall and ceiling decoration and wall grille. |

What I knew as the College Board Building in 2014 was so named because it housed the offices of the College Board Corporation, but the College Board Corporation did not move there until 1984. Prior to that it was built as an innovative parking garage and then became the Sofia Brothers Warehouse for almost fifty years. “[...The] facade of the Sofia Brothers warehouse at Columbus Avenue and West 61st Street...reflected the self-conscious sense of elegance that characterized some of the West Side's best-known apartment buildings.” (Lee A. Daniels, “ABOUT REAL ESTATE; AN ART DECO WAREHOUSE BECOMES A CONDOMINIUM”, The New York Times, May 25, 1984; http://www.nytimes.com/1984/05/25/business/about-real-estate-an-art-deco-warehouse-becomes-a-condominium.html)

|

| The College Board building entrance (2014), Columbus Avenue between 61st and 62nd Streets. |

When this building was first opened as an automatic parking garage in 1930, cars would enter through this entrance and be taken to the elevator tower on the 61st Street side of the building. (Joanna Mercuri, “Fordham Offices Move to New Location on Columbus Avenue”, Fordham News, August 11, 2015; http://news.fordham.edu/university-news/fordham-offices-move-to-new-location-on-columbus-avenue/#prettyPhoto)

|

| (1936 photo credit: Joanna Mercuri, “Fordham Offices Move to New Location on Columbus Avenue”, Fordham News, August 11, 2015; this photo can also be seen in the lobby of this building.) |

“In the late 1920s, Milton A. Kent, a Westchester life insurance salesman with a big idea, got financial backing for his Kent Automatic Garage, building high-rise garages on 44th [Street] east of Third [Avenue], and at 61st [Street] and Columbus [Avenue], the latter with spectacular polychrome terra cotta.” (Christopher Gray, “Streetscapes: For the Car, and Far From Pedestrian”, The New York Times, September 9, 2010; http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/12/realestate/12scapes.html) The Kent Garage was designed by the architectural firm of Jardine, Hill & Murdock in 1929-30.

“[T]he garage used a patented automatic parking system in which an electrical ‘parking machine’ engaged cars by their rear axles and towed them from the elevator platform to parking spots.” (Landmarks Preservation Commission Designation List 164, LP-1239, April 12, 1983, p. 1) Although Kent went out of business in 1931, the building remained a parking garage until 1943 when the Sofia Brothers acquired the property. It then became a warehouse for the Sofia Brothers Moving and Storage Company.

|

| Two doors on West 61st Street. The entrance on the left goes to the Sofia’s 1985 lobby. |

The Sofia Brothers Moving and Storage Company originated in the Bronx. In 1900 Theodore Sofia and his wife, Theresa Sofia, lived at 1221 Intervale Ave., the Bronx. They were immigrants from Italy..., and they had eight children. ...The family maintained a boarding and livery stable at this address[, and this] stable was the origin of the...moving and storage business. The brothers in the business were Charles..., Frank..., Patrick..., James..., Theodore..., and John... .” (http://www.waltergrutchfield.net/sofia.htm)

After the building facade was designated a New York City Landmark in 1983, the interior was redesigned as luxury apartments and windows were added to the south side--the elevator tower side--of the building. The building became "The Sofia" in 1984. The lobbies, however, were not given landmark status.

|

| The entrance to the Sofia Apartments on West 61st Street leads to this lobby. This lobby was probably decorated in this style after 1985. |

|

| A 2014 photo of the Columbus Avenue entrance. |

The building was purchased in 2014 by Fordham University and is now called Martino Hall. Martino Hall houses “the department of communication and media studies, the Office of Career Services, International and Study Abroad programs (ISAP) and administration for the Gabelli School of Business, among other programs and offices.” (Connor Mannion, “Martino Hall: A History”, The Fordham Observer, February 14, 2016; http://www.fordhamobserver.com/martino-hall-a-history/) If it once had an Art Deco lobby, that lobby no longer exists.

|

| The lobby of Fordham’s Martino Hall (2016). |

*****

LINKS TO MY PREVIOUS ARTICLES:

ARCHITECTURAL MURALS OF LUMEN MARTIN WINTER and a REPORT ON THE EMPIRE STATE DAIRY BUILDING

read more...

The Heart of the Park: Bethesda Terrace and its suspended Minton Tile ceiling

read more...

A Landmarks hearing was held on July 19, 2016...

read more...

Two Restorations: The City Hall Subway Station and the Tweed Courthouse

read more...

Egyptian, Moorish and Middle Eastern Ornamentation Used In Art Deco Terra Cotta in New York City, and Empire State Dairy Update

read more...

The Heart of the Park: Bethesda Terrace and its suspended Minton Tile ceiling

read more...

A Landmarks hearing was held on July 19, 2016...

read more...

Two Restorations: The City Hall Subway Station and the Tweed Courthouse

read more...

Egyptian, Moorish and Middle Eastern Ornamentation Used In Art Deco Terra Cotta in New York City, and Empire State Dairy Update

read more...

Inside Prospect Park: The park's Rustic, Classical and other Internal Architecture

read more...

Herman Carl Mueller in Titusville and Trenton, New Jersey; A Charles Volkmar Discovery in Clifton, New Jersey

read more...

A Book Review and New Discoveries and Updates-II: Jean Nisan, Ceramic Tile Artist

read more...

Polychrome Terra Cotta Buildings in Newark, New Jersey

read more...

New Discoveries-I: The Tiled House of Jere T. Smith

read more...

Introducing the Stained and Dalle de Verre Glass Art of Robert Pinart

read more...

Bits and Pieces: Polychrome Terra Cotta- and Tile-Clad Buildings

read more...

Socialist and Labor Architecture and Iconography in New York City

read more...

Bits and Pieces: Two Mosaics--Hamden, CT and Manchester, NH

read more...

The Renaissance Casino and Ballroom Complex in Harlem: Another Tunisian Tile Installation Headed for Demolition

read more...

Clement J. Barnhorn and the Rookwood Pottery

read more...

The Woolworth Building

read more...

The Mosaic Art of Hildreth Meière

read more...

Lost Tile Installations: The Tunisian Tiles of the Chemla Family

read more...

The Grueby Children's Murals on East 104th Street

read more...

The Experimental Lustre Tiles of Rafael Guastavino, Jr.

read more...

Bits and Pieces: Two "E"s--Eltinge and Elks; and more about Jean Nison

read more...

The Ceramic Tiles and Murals of Jean Nison

read more...

Pleasant Days in Short Hills: A Rookwood Wonderland

read more...

Architectural Ceramics in the Queen City

read more...

Isaac Broome: Innovation and Design in the Tile Industry after the Centennial Exhibition

read more...

"Immigration on the Lower East Side": A Public Arts Mural Created by Richard Haas

read more...

Movie Palaces-Part 2: The Loews 175th Street Theatre

read more...

Béton-Coignet in New York: The New York and Long Island Coignet Stone Company

read more...

Michelin House, London

read more...

Movie Palaces, Part 1: Loew's Valencia Theatre

read more...

An Architectural and Ceramic Tour of Istanbul - Part II

read more...

The Tiles of Fonthill Castle

read more...

An Architectural and Ceramic Tour of Istanbul - Part I

read more...

Tiled Facades in Madrid

read more...

Nineteenth Century Brooklyn Potteries

read more...

Ernest Batchelder in Manhattan

read more...

Leon Victor Solon: Color, Ceramics and Architecture

read more...

Architectural Art Tiles in Reading, Pennsylvania

read more...

Charles Lamb and Charles Volkmar

read more...

Kansas City Architecture - II

read more...

Kansas City Architecture - I

read more...

Westchester County--Atwood and Grueby

read more...

Modern Houses in New Caanan, Connecticut

read more...

PPG Place, Pittsburgh

read more...

Aluminum City Terrace, New Kensington, Pennsylvania

read more...

Newark's WPA Tile Murals: “Fine Art is an Important Part of Everyday Life”

read more...

Public Art Programs in New York City: The CETA Tile Murals at Clark Street

read more...

Concrete and Tiles-I: Moyer, Mercer, Murosa

read more...

The Café Savarin and the Rookwood Pottery; Chocolate Shoppe Rebounds

read more...

Architectural Ceramics of Henry Varnum Poor

read more...

Herman Carl Mueller and the Church of St. Thomas the Apostle

read more...

Meet Me at the Astor

read more...

The Mikvah Under 5 Allen Street; "Historic Hall" Apartments Revisited

read more...

London Post-3

read more...

Some Moravian Tile Sites in New York

read more...

London Post-2

read more...

London Post-1

read more...

Brooklyn's International Tile Company

read more...

Subway Tiles-Part III, the Squire Vickers Era

read more...

Subway Tiles-Part II, Heins and LaFarge

read more...

Subway Tiles--Part I, Guastavino tiles

read more...

Trent in New York-Part III, Historic Hall Apartment House

read more...

American Encaustic Tiling Company-Part II, Artists' Tiles

read more...

Trent in New York-Part II, a Dey Street Restaurant

read more...

American Encaustic Tiling Company-Part I, Tile Showrooms

read more...

Trent in New York-Part I, The Bronx Theatre

read more...

Fred Dana Marsh's Tiles

read more...

*****

About this blog:

This is a non-commercial, educational blog. Content is compiled/written by Michael Padwee and all opinions expressed herein are my own, or quoted, and are offered without intending to harm any person or company.

I fact-check as carefully as possible before posting and try diligently to cite sources of text and photos that are not my own.

I reserve the right to edit content—either add or delete material—as I see fit.

If you find a broken link on this blog, please contact me at mpadwee'at'gmail.com.

I do not accept anything of value to write about products or businesses. If I recommend a product or a company, it is strictly not for profit.

Permission is granted to link back to this site. In fact, link backs are appreciated.

Offensive comments or spam will be deleted. I reserve the right to decide what is considered offensive.

I am not responsible, nor will I be held liable, for blog comments. Writers of comments take full responsibility for their content.

I reserve the right to remove comments asking for appraisals or trying to sell items. (Click on "comments" in the section below to leave a comment.)