I recently entered two photos in the Labor Heritage Foundation "Occupy Now!" photography contest. One submission, "Rise Up-We Are The 99%" won first prize for amateurs. (http://www.laborheritage.org/?p=2544)

|

| More of my photos are at http://michaelpadweephotos.weebly.com/. |

Now, the subway tiles:

|

| A Grueby Eagle on the 33rd Street #6 platform (2012) |

In 1901 a section of wall of what was to become the Columbus Circle station was set aside so ceramic and other companies could install their wares for inspection by the Rapid Transit Commission. (The New York Times, May 26, 1901) Among these companies was the American Encaustic Tiling Company, which was hoping to obtain a contract to tile the subway stations' walls with plain tiles. According to a plaque in the Columbus Circle station, "Though these American Encaustic wall tiles were not selected, the company produced decorative tiles and mosaics for many original 1904 IRT stations, and larger plaques for stations built in the 1910s."

|

| Plaque in the Columbus Circle station that explains the AET exhibit. The wall at the top is where the tiles were exhibited. (Photo courtesy of Michael Padwee) |

"Another keyhole to the past opened recently on the uptown platform of the No. 1 train at the...Columbus Circle station...: an interwoven guilloche pattern--...in red and yellow mosaic tiles. ...Next to the guilloche border is a large blue-gray mosaic medallion, enclosing a four-lobed pattern known as a quatrefoil. ...In 'Silver Connections' (1984), his monumental history and description of the New York subway, Philip Ashforth Coppola...wrote '[in 1901]...architects used its [Columbus Circle Station's] walls as an art gallery, experimenting with decorative ideas... .' After their brief service..., 'all these preliminary experiments were covered over and forgotten.'" (David W. Dunlap, "Behind an Old Subway Wall, a Glimpse of an Even Older One", The New York Times, October 20, 2010, http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/10/20/antique-mosaic-comes-to-light-not-far-from-where-the-coliseum-stood/)

From the first contract to build a subway system in 1900 there was an emphasis on art in public areas. William Barclay Parsons, the chief engineer of the Rapid Transit Commission, hired George Heins and Christopher LaFarge as consulting architects for the IRT subway system. (Lee Stookey, Subway Ceramics: A History and Iconography, published by Lee Stookey, Brooklyn, NY, 1992, p. 14)

"All of the station...[construction] was designed by the engineers of the Rapid Transit Board under Parsons' direction. The raw brick walls and concrete ceilings were then turned over to Heins and LaFarge to be 'beautified.' The decorative scheme that they devised was certainly influenced by Parsons... . Heins and LaFarge's plans were subject to the final approval of Parsons, who delegated authority to D. L. Turner, assistant engineer in charge of stations for the Rapid Transit Subway Construction Company. August Belmont also oversaw station decoration; he approved of the first completed station at Columbus Circle, but complained of the use of too much brick at Astor Place, 50th Street, and 66th Street. [Heins and LaFarge had designed the Zoo in the Bronx and] ...carried several techniques from that project into the subway. These included Guastavino arches and vaulted ceilings, polychrome tile, and ornamental figures... .

|

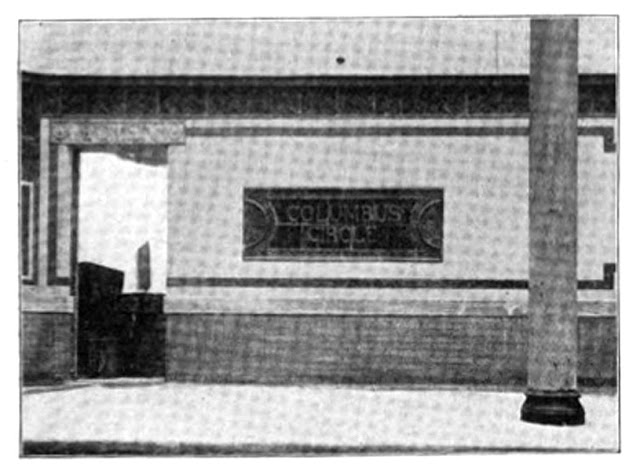

| How a subway station wall area originally looked. ("Subway Stations in New York City", Brick, Vol. XIX, No. 3, September 1903, p. 93) |

Original station decorative scheme

"In general, the station finish consisted of a sanitary cove base that made the transition from floor to wall, upon which rested a brick or marble wainscot for the first two and one-half feet or so of wall area. This wainscot was applied to withstand the hard usage that the lower wall would be subjected to. The wainscot was completed by either a brick or marble cap, and the remainder of the wall area was covered with three by six-inch white glass tiles, completed near the ceiling by a cornice or frieze. The wall area was divided into fifteen foot panels, the same spacing as the platform columns, by the use of colored tiles or mosaic... . The full station name appeared on large tablets of either mosaic tile, faience, or terra-cotta at frequent intervals, while smaller name plaques were incorporated into the cornice every fifteen feet. Sharp corners were eliminated and junctions between walls were curved to prevent chipping and facilitate cleaning. ...the stations exhibit considerable variation in color and detail. A conscious effort was made by the architects to create a distinct wall treatment for each station, both to relieve monotony and assist in the identification of different locations, and the 'extent of the decoration varies with the relative importance of the stations.' Wherever possible, a local association was worked into the decorative scheme, such as the seal of Columbia University at 116th and Broadway. Heins and LaFarge used a number of different details to add interest to the stations." (Architectural Designs for New York's First Subway, David J. Framberger, Survey Number HAER NY-122, pp.365-412, Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service, Department of the Interior, Washington, DC 20240) |

| A Grueby "Santa Maria" tile plaque at the IRT 59th Street/Columbus Circle platform (2012) |

Grueby Faience

|

| A Grueby Faience ad in the 1905 Catalogue of the Twentieth Annual Exhibition of the Architectural League of New York. |

Heins and LaFarge also worked with designers and producers of ceramics. Two of the most prominent were William M. Grueby of the Grueby Faience Company of Boston, and William Watts Taylor, president of the Rookwood Pottery of Cincinnati, Ohio. "...Grueby...was responsible for many of the distinctive early plaques: the ship at Columbus Circle, the eagle at 33rd Street, the beaver at Astor Place and a similar plaque for 50th Street, wreath-like medallions at 116th Street and 14th Street..., and the blue oval sign at Bleecker Street...[,] also...the heavy-bordered name panel at 28th Street and smaller letter and number signs and medallions at Brooklyn Bridge, 18th Street..., 42nd Street, 103rd Street, and 110th Street." (Lee Stookey, Subway Ceramics: A History and Iconography, published by Lee Stookey, Brooklyn, NY, 1992, p. 16)

|

| Astor Place Beaver plaque. 2012 photo, Michael Padwee |

In March 2000 a Grueby beaver plaque was going to be auctioned off by the Cincinnati Art Galleries in Cincinnati, Ohio. According to its description it was "formerly of the New York Subway System...[i]nstalled, circa 1905, at Astor Place Station...[and r]emoved during [an] official renovation sometime in the 1960s... . The tile measures 25 by 14 inches and is signed 'MC+' on its right side in green slip." (Lot 120, "Art Tile Auction, March 1 Thru 9, 2000" [catalog], Cincinnati Art Galleries, Cincinnati, Ohio) Although this historic plaque had been sold previously and had been part of a joint exhibit by a gallery and a museum, it wasn't until this auction that a number of people thought the tile might actually belong to the City of New York and demanded that it be pulled from the auction.

|

| Another renovation in 2012, but the Grueby plaques remain. (Photo courtesy of Michael Padwee) |

|

| An Atlantic Terra Cotta letter-cartouche at Canal Street |

Atlantic Terra Cotta Company

Along with Rookwood and Grueby "...the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company...joined the project...[and was] responsible for shield-like cartouches at Canal Street, Worth Street..., Spring Street and Third Avenue in the Bronx. Atlantic Terra Cotta also produced small number panels for several stations...by ingenious mass-production: a standard plaque, bordered with cornucopias, was designed to receive a separately molded panel with the street number...on it. Examples can be seen in several stations including 86th Street, 137th Street, 145th Street and 157th Street." (Lee Stookey, Subway Ceramics: A History and Iconography, published by Lee Stookey, Brooklyn, NY, 1992, p. 16)

|

| A mass produced, Atlantic Terra Cotta Company cornucopia and street number panel |

"During the first quarter of the 20th century the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company was the largest producer of architectural terra cotta in the world. By 1908 the firm operated four plants including Perth Amboy and Rocky Hill, N.J.; Staten Island, N.Y. and Eastpoint, Ga. (near Atlanta). The company maintained branch offices in New York, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Dallas and Newark, N.J. William H. Wilson presided as company president during peak years of production.

National production of terra cotta quadrupled from 1900 to 1912, and the industry prospered throughout the 1920s. Terra cotta provided the ideal facade for the high rise, metal skeletal, constructed buildings. Atlantic Terra Cotta manufactured products for forty percent of the terra cotta buildings in New York City...", as well as for the subway system. The company closed in 1943. (http://www.lib.utexas.edu/taro/utaaa/00038/aaa-00038.html)

Hartford Faience

Both William Grueby and Eugene Atwood worked for the Low Art Tile Works in Chelsea, Massachusetts in the 1880s. They formed a partnership in an architectural faience company in 1891, and in 1894 Atwood formed the Atwood Faience Company of Hartford, Connecticut, which later became the Hartford Faience Company. At the same time Grueby formed his own company in South Boston. (Susan J. Montgomery, The Ceramics of William H. Grueby, Arts and Crafts Quarterly Press, Lambertville, NJ, 1993, pp. 13-16) Hartford Faience supplied some of the plaques and cartouches for at least the Borough Hall Station in Brooklyn, and the South Ferry Station in Manhattan.

|

| `From "Hartford" Faience and Tiles 1910, a reprint of an original catalog, owned and published by Antique Articles, artiles@antiquearticles.com, c. 2000 |

|

| A Borough Hall (Brooklyn) plaque and surrounding mosaic tiling |

Hartford Faience was at it's high point about 1904 when the company participated in the St. Louis World's Fair with an impressive display that included it's famous "Sun (or "Fire") Worshipers" fireplace panel.

|

| 9' x 5' "Sun-Worshipers" or "Fire-Worshipers" panel |

Rookwood Faience

The Rookwood Pottery Company of Cincinnati, Ohio created a number of the tile plaques and other tile ornamentation in some Heins and LaFarge stations. Rookwood's company records note that the pottery's faience division was responsible for the 23rd, 79th, 86th, and 91st Street stations and the large plaques at Wall and Fulton Streets. (Lee Stookey, Subway Ceramics: A History and Iconography, published by Lee Stookey, Brooklyn, NY, 1992, pp. 16+)

|

| A Rookwood plaque and faience "W" panel installed at the Wall Street IRT #6 station |

"Maria Longworth Nichols Storer founded Rookwood Pottery in 1880 as a way to market her hobby - the painting of blank tableware. Through years of experimentation with glazes and kiln temperatures, she eventually built her own kiln, hired a number of excellent chemists and artists who were able to create high-quality glazes of colors never before seen on mass-produced pottery." (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rookwood_Pottery_Company)

|

| A picture post card from the author's collection |

"In 1883, Nichols hired William Watts Taylor (1847-1913) as the general business manager of Rookwood pottery. Taylor’s goals for Rookwood echoed those of [William] Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement which was to restore quality and integrity to the arts. Taylor was adamant about nurturing innovative ideas and even commissioned leading chemists, such as Karl Langenbeck (1861-1938), to aid in the development of new glazes. The results were the extraordinary glazes that were at the time exclusive to Rookwood pottery. It was under Taylor’s command that Rookwood would reach the summit of its success." (Daneel S. Smith, "Rookwood Pottery as 'Fine Art'", http://journal.utarts.com/articles.php?id=1&type=paper)

"In 1902, Rookwood added architectural pottery to its portfolio. Under the direction of Watts Taylor, this division rapidly gained national and international acclaim. Many of the flat pieces were used around fireplaces in homes in Greater Cincinnati and surrounding areas, while custom installations found their places in grand homes, hotels, and public spaces. Even today, Rookwood tiles decorate Carew Tower, Union Terminal (Cincinnati) and Dixie Terminal in Cincinnati, as well as the Rathskeller Room in The Seelbach Hilton in Louisville, Ky. In New York, the Vanderbilt Hotel, Grand Central Station, ...Lord and Taylor and several subway stops feature Rookwood tile designs." (From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rookwood_Pottery_Company)

|

| A slightly damaged Rookwood plaque and faience "F" panel at the Fulton Street IRT #6 platform |

Both Rookwood and Grueby have "decorated" other railway facilities throughout the country. Rookwood faience tiles were used in the Oregon-Washington Railroad and Navigation Company Terminal in Spokane, Washington in 1913, and Grueby faience tiles were used in Scranton, Pennsylvania for the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad. In 1908 the DL&W dedicated what was to be its "star [terminal]. ...the palatial structure housed one of the most important art tile installations in America--a frieze that circles the waiting-room and consists of thirty-six murals composed of Grueby Faience tiles. Each mural depicts a scene along the railroad's lines beginning at the Hoboken Ferry slips...and ending at Niagara Falls... ." All the panels are two feet high and four to nine feet long. The railroad waiting room is now a restaurant. The story of these murals, written by Dr. Richard D. Mohr and photographed by Robert W. Switzer, can be found online at http://www.aapa.info/ Portals/0/ Lackawana.pdf where this information was obtained.

|

| A view of the D, L & W waiting room with the panels below the balcony in a 1909 photograph, and one of the Grueby panels, below. |

For information and photos about "everything" NYC subways check out http://www.nycsubway.org/.

In another post I will discuss the subway tiling during the Squire Vickers era of construction.